Analyzing syntax across three languages is a huge undertaking that the scope of this project didn't let us analyze fully. However, there are some preliminary conclusions that can be drawn from side-by-side comparison of syntax trees across languages. Here is a quick overview of how the visualizations are structured:

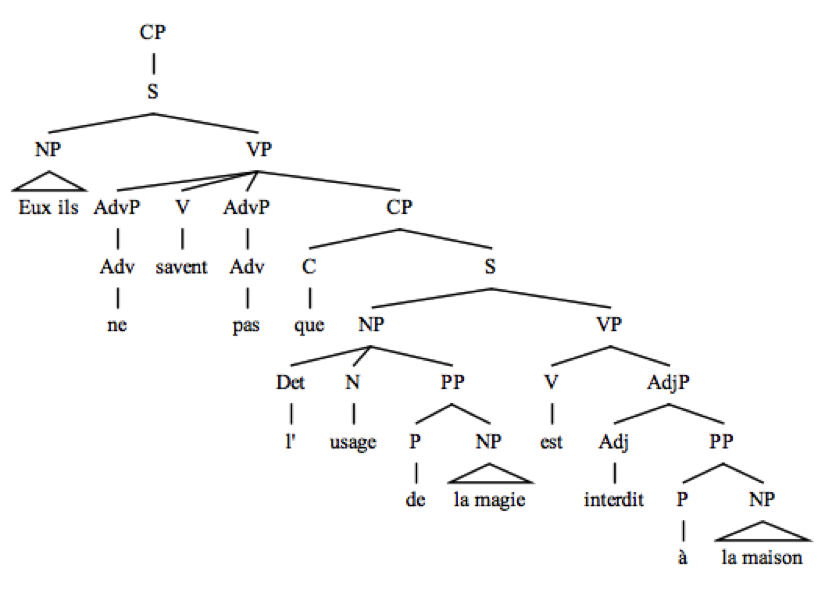

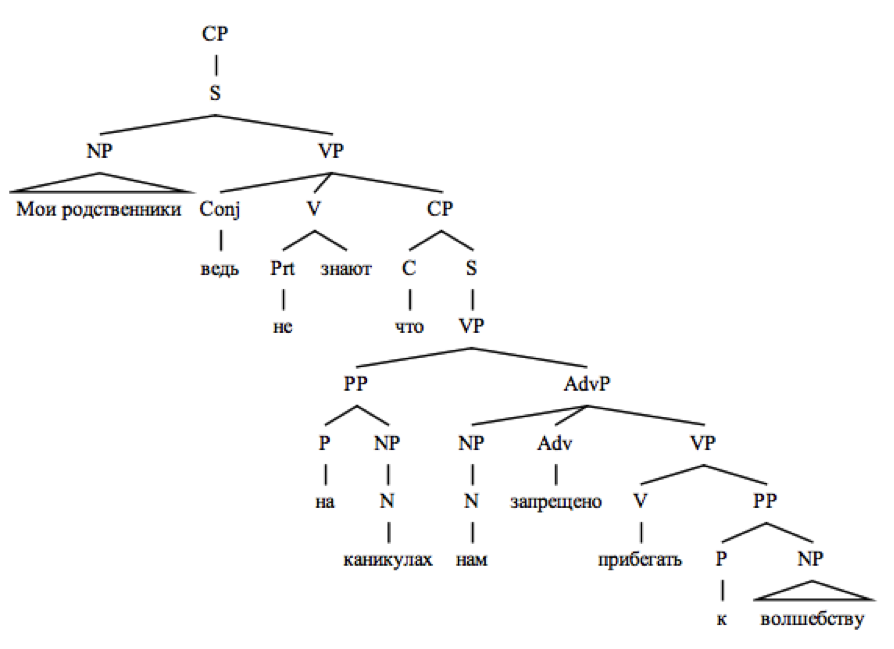

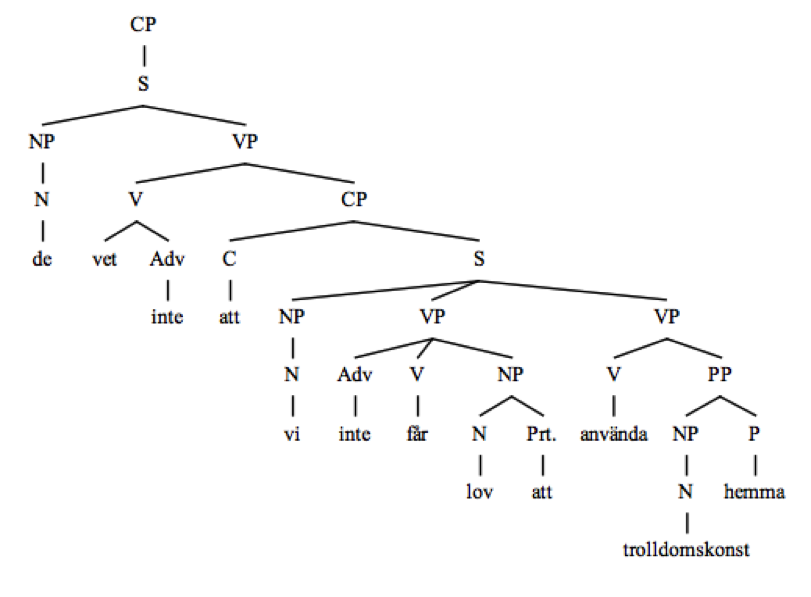

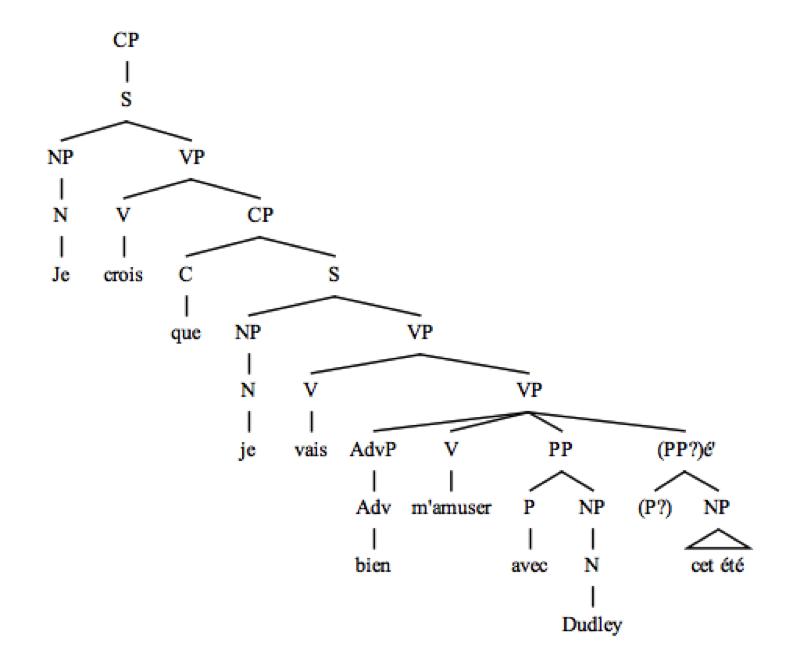

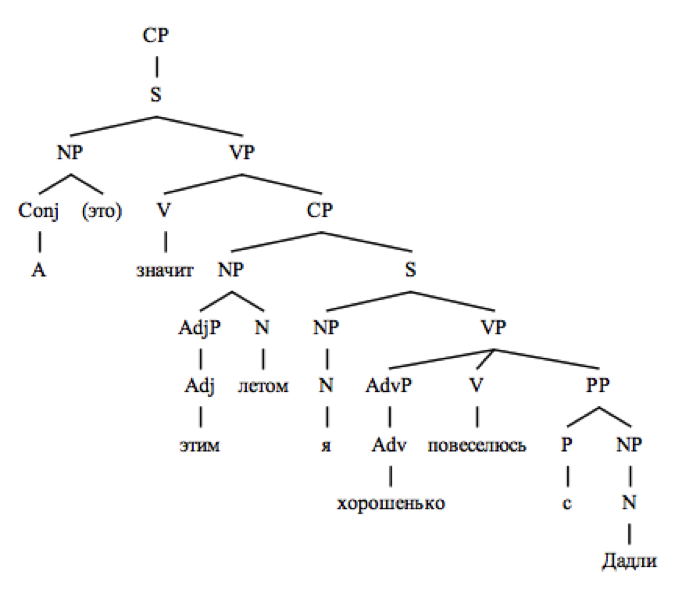

Syntax "trees" always begin with the CP node, which stands for complementizer phrase. Basically, this is a meta-superstructure that allows sentences to nest inside each other. A phrase is the higher element in a syntax tree, and must always contain the element it's named for. So, a complementizer phrase always has a complementizer node [C], though that is sometimes omitted in the below trees for simplicity's sake when empty. CPs contain the S element, meaning "sentence", which has two child nodes: NP [noun phrase] and VP [verb phrase]. NPs must contain the element N [noun] but can also have other elements, such as adverb or adjective phrases [AdvP, AdjP] or, most commonly, prepositional phrases [PP]. VPs must also contain a verb [V] and can include AdvP, AdjP, or PP. VPs can also contain a child CP element, which allows a sentence to be embedded inside another. Other elements might include auxiliary verbs [Aux] or conjunctions [Conj], which aren't too terribly important.

Click on the sentences below to show/hide their syntax trees.

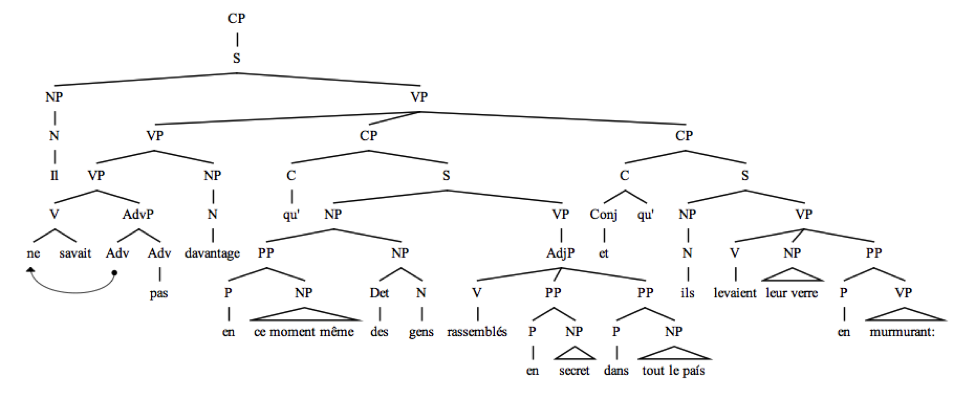

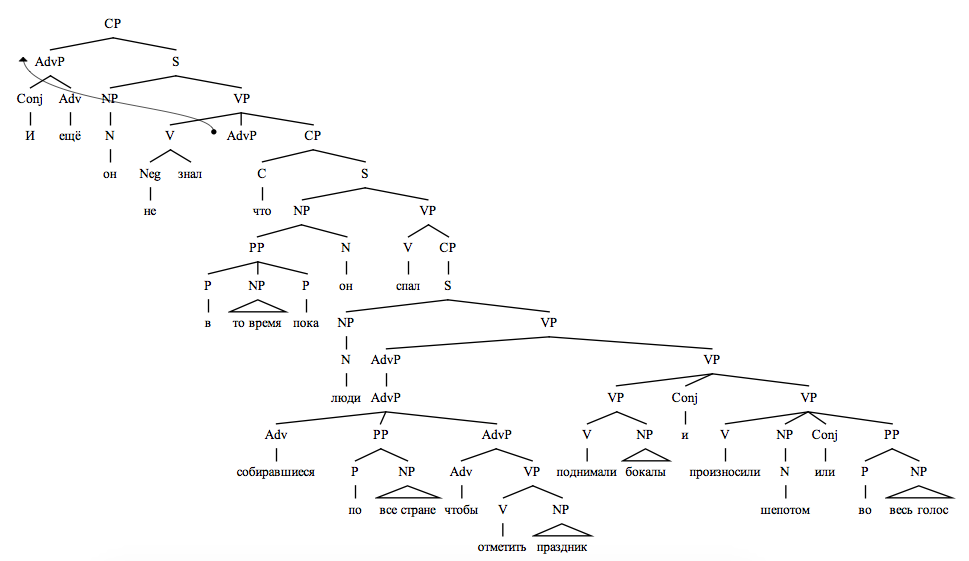

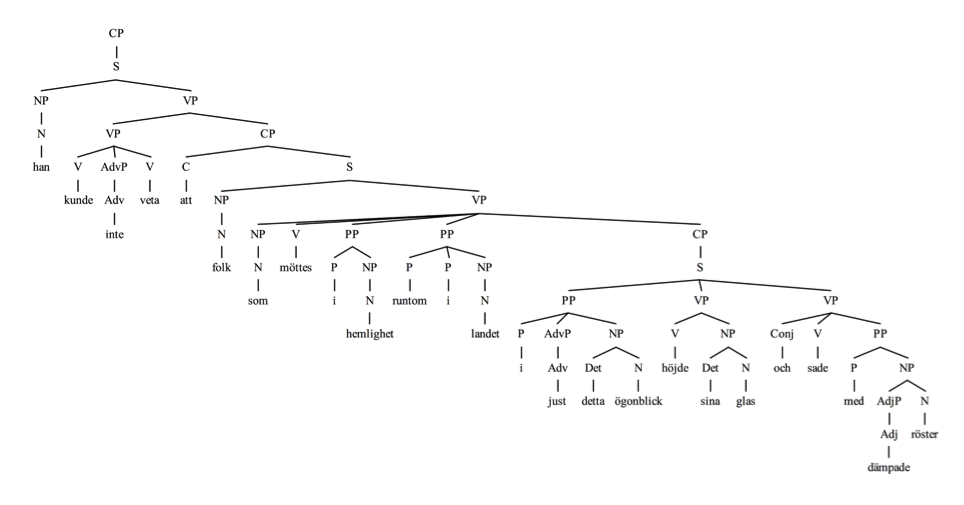

This is the last sentence of the first chapter in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone. The English above is rendered in several ways in the three languages studied (in order: French, Russian, and Swedish). In French, the main VP houses two CP children along with the central VP and its direct object NP. In Russian, two CPs are also nested inside the main VP. Swedish also has two nested CPs, though the middle one is rather complicated and allows its VP to house an NP and two PPs along with the main V element. To conclude, the sentence is equally complicated in all three languages, and has the same number of CPs inside the "sentence" to represent the clauses that are distinct across the three languages.

Il ne savait pas davantage qu'en ce moment même, des gens s'étaient rassemblés en secret dans tout le pays et qu'ils levaient leur verre en murmurant:

И еще он не знал, что в то время, пока он спал, люди, тайно либо открыто собиравшиеся по всей стране, чтобы отметить праздник, поднимали бокалы и произносили шепотом или во весь голос:

Han kunde inte veta att folk, som möttes i hemlighet runtom i landet, i just detta ögonblick höjde sina glas och sade med dämpade röster:

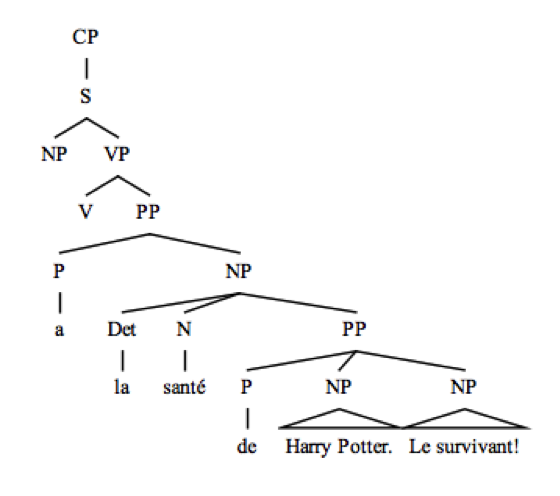

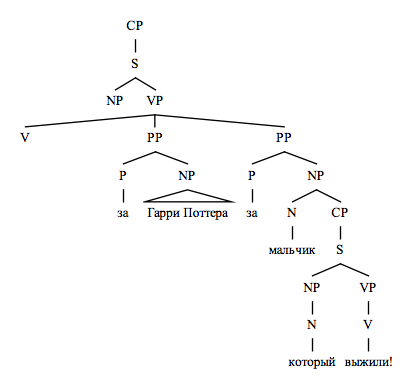

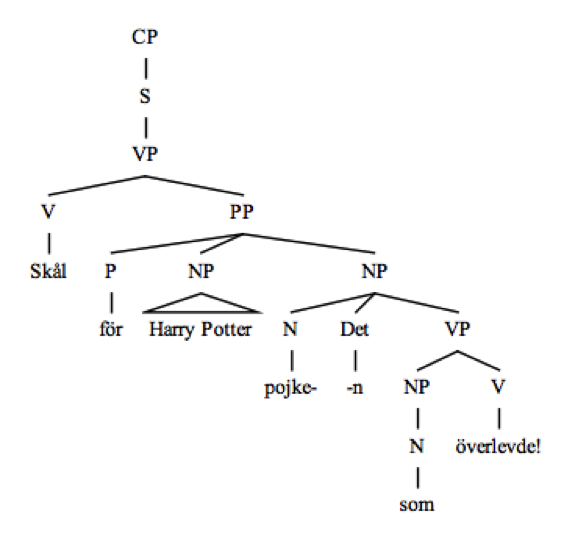

This sentence displays the differences in syntax used to toast or celebrate in each language. Interestingly, none of the languages have anything in the NP or V, as toasting generally involves an implied "We toast..." or "We drink..." and then the following "to Harry Potter, the boy who lived!" Only the toast itself was written, which is represented by one PP in French and Swedish, and two PPs in Russian. The trees are distinct in that Swedish does have a verb in the V element, and Russian actually embeds a CP for the second part of the toast, "to the boy who lived" = "за мальчика, который выжил". Russian который phrases always embed a CP - in this case, the который phrase expands upon мальчик, the boy they're toasting.

« A la santé de Harry Potter. Le survivant ! »

За Гарри Поттера за мальчика, который выжил!

Skål för Harry Potter - pojken som överlevde

This sentence is another case of embedded clauses. The first part of the sentence, "They don't know," is a clause on its own, with the rest following as an embedded CP. In all three languages, the C element must be filled to link these two clauses, unlike the meta-superstructure CP that usually has an empty C node at the very top of the sentence.

Eux, ils ne savent pas que l'usage de la magie est interdit à la maison.

Мои родственники ведь не знают, что на каникулах нам запрещено прибегать к волшебству.

De vet inte att vi inte får lov att använda trolldomskonst hemma.

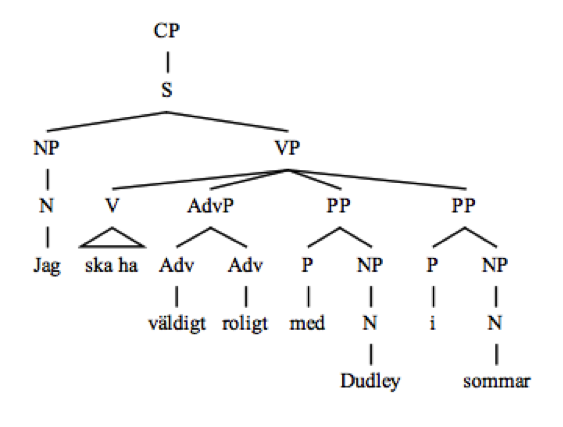

This sentence is the last in the book, which is part of the reason we chose to diagram it. It's interesting to note, though, how neatly embedded the clauses are in French and Russian, while Swedish uses different phrases under the same VP to modify the main verb without introducing another clause.

Je crois que je vais bien m'amuser avec Dudley, cet été.

А значит, этим летом я хорошенько повеселюсь с Дадли…

Jag ska ha väldigt roligt med Dudley i sommar…